My first experience with Prilepin’s chart was in the summer of 1993. I had entered my first powerlifting competition in the spring of that same year and had bombed out in the squat. I didn’t give up and did the right thing by seeking out professional help, not psychiatric mind you (although I may have needed it). I sought out a powerlifting coach.

My search brought me to Mike’s Olympic Gym in Mechanicsville, Virginia. I had a job painting houses that summer and worked 10 hours a day. I lived an hour (one way) from Mike’s so I knew that if I were going to get any stronger, I’d have to go where the strong go. In Richmond, it was Mike’s. My training up to that point was progressive overload. I would do a set of eights one week, and depending on how I felt, I would go up five to 10 pounds for the next week when I went to a set of seven. At the time (and I think to this day), Mike Craven would handwrite all of the programs for his members. Mike is without a doubt the most passionate and intense person I know when it comes to strength training. He networked with individuals like John Gamble (former strength coach for UVA who is now with the Miami Dolphins) and Fred Hatfield (otherwise known as Dr. Squat). This was all well before the internet so networking wasn’t nearly as easy.

He gave me my program, and there were percentages all over it. I was amazed. After a few weeks, I got up the courage to ask where he got his information. He showed me Managing the Training of Weightlifters by Nikolai Petrovich Laputin and Valetin Grigoryevich Oleshko and explained that the information was based on experiments with thousands of lifters in the former Soviet Union. I trained at Mike’s for a few years and then left to try my hand at bodybuilding. After seeing the error of my ways, I went back to powerlifting. I read Powerlifting USA and had seen Louie’s articles on training and was interested in his ideas. However, after seeing his ad for the reverse hyper and then an article about one of his own products, I was disenchanted and believed that he was simply trying to sell something.

Fast forward to 1998, I was working as Virginia Commonwealth University’s first strength and conditioning coach and had spent the last five years looking for Prilepin’s chart. Then low and behold, I received a new edition of PLUSA. In it, Louie had an article titled, “HIT …or Miss?” which discussed percentage training and beside that, Prilepin’s chart. I knew once I saw the famous chart in Louie’s article that he did know what he was talking about and wasn’t full of it. This revolutionized my training as well as the way I trained VCU’s athletes.

There have been articles written in the past about Prilepin’s chart. However, it has been over 10 years since this information was reviewed. I’ve been asked several questions about the chart and how it can be used with beginners.

What is it?

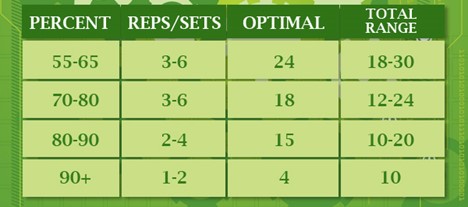

Prilepin’s chart gives set percentages of one’s max to be used in training. Here’s what it looks like:

PRILEPIN’S CHART

Basically, the Russians would take a percentage of your contest max. Let’s say 70 percent. They assigned reps and sets to this percentage and would then have a lifter perform the classic lifts at this percentage. They looked at what happens to the speed of the bar, the lifter’s form, and the lifter’s next contest max. From this research, they decided what sets and rep schemes would work with a given percentage. For instance, if they had a lifter perform 70 percent of his contest max, they found that if the lifter did 3–6 reps per set, he would get a positive training result (i.e. he had good form, his bar speed was good, and his max went up).

They also found that if the lifter only did two reps per set it wasn’t enough. Either there wasn’t enough of a stimulus (there wasn’t enough weight on the bar) or the bar would move too fast (kind of like trying to throw a ping pong ball as hard as you can). Because of this, the lifter’s form would break down. They also found that if the lifter did more than six reps per set, the lifter’s form would break down from fatigue, which would in turn train bad habits, and the bar would move too slow (if you train slow you become slow). The Russian’s found that a lifter could do anywhere from 2–8 sets depending on how many reps per set the lifter did. In other words, a lifter could do:

8 sets of 3 (24)

or

2 sets of 6 (12)

or

4 sets of 3 (12)

or

5 sets of 3 (15)

The combinations are nearly endless. Why the broad range? Well, the Russians realized that everyone reacts differently to a training program. So, if I react better to higher reps, I would do six reps per set. But if you react better to low reps, you would do three reps per set. Prilepin also knew that in training there will be good days and bad days. If you were scheduled to do six sets of three but you’re killing it, you can keep it going and do up to (but not beyond) eight sets. The same holds true if things aren’t going your way. For example, you had a rough night of sleep or the kids kept you up. Whatever the case may be, if you’re grinding it out, only do four sets.

Considerations

These experiments were done on Olympic weightlifters. Why is that important? Because that’s all they did. They didn’t run. They didn’t play football. They didn’t throw baseballs. They lifted. So you need to account for this in your program design. In other words, you’re probably better off going toward the low end of the total rep range rather than the high end. However, you can look at where you are in your season as well. If our athletes are in-season, we’ll go even lower than the prescribed number of total reps. For out of season, we bring it back up toward the higher end of the range.

These percentages are based off of a contest max. The lifters were lifting as if (and sometimes it was true) their life depended on it. So the Bulgarians actually use two separate sets of maxes—their contest max and their training max. The training max is something done in the gym. I’m sure you’ve heard of this—you have your contest max and your gym max. Your contest max should be higher than you gym max. If it isn’t, you could be conservative, your gym lift may be questionable, or your training may be flawed.

You also should take into account that when the power lifts (squat, bench, and deadlift for those of you who STILL don’t know) are done for a max move, they are done much slower than with the Olympic lifts. This can be more taxing on the CNS.

Why are the percentages in the Westside template so different from Prilepin’s chart?

Olympic lifters don’t wear supportive gear. Ever seen someone in a snatch shirt? Although it would be funny, I don’t think it would be effective. So what you say? You must lower your training weights when not wearing your gear. Let’s look at this practical situation.

Your best raw squat = 400 lbs

70% of 400 lbs = 280

Let’s say you get 100 lbs out of your squat suit and your knee wraps (which is definitely possible even in the USAPL), which moves your contest max to 500 lbs.

500 lbs X 70% = 350

That’s 70 more pounds that you don’t have from the gear. So you move the percent down.

500 lbs X 56% = 280

Many of the programs that the Westside lifters use incorporate band and chains. When accounting for this, Louie and Dave Tate count only the band tension at the bottom. So let’s say you get 50 lbs of band tension at the bottom. Now we need to drop our training weight down to about 230 lbs.

500 lbs X 47% = 235 = our first week of dynamic box squats

500 lbs X 47% = 235 + 50 pounds of band tension at the bottom = 285

285 = about 70% of your non-equipped max

If you ever go to one of the EliteFTS seminars or have the opportunity to talk with Louie or any of the staff from EliteFTS, they will explain all of this to you. But it can get confusing.

So how do you use this with athletes?

So that I don’t lose the reader, I’ll only discuss the use of Prilepin’s chart with beginners in regards to the squat. First a couple of definitions:

Beginner: someone who hasn’t lifted for one full year at VCU

Intermediate: someone who has had at least one full year of training with us at VCU or is advancing quickly (training age, maturity, previous collegiate lifting experience)

We follow the basic Westside template with our intermediate athletes, and we have a lower and upper max effort day and a lower and upper dynamic day (for more information on this, read Dave Tate’s Periodization Bible parts I and II).

Beginner athletes will follow progressive overload for three weeks. The coach will handwrite the weights based on how the athlete did that week with a given weight. If their technique looks good, we go up. If they have difficulty with the weight or the technique, they stay at that weight until the technique is mastered. We then test using anywhere from a three to a five rep max (I know it’s not a true max, but it give the coaches and the athlete something to go by).

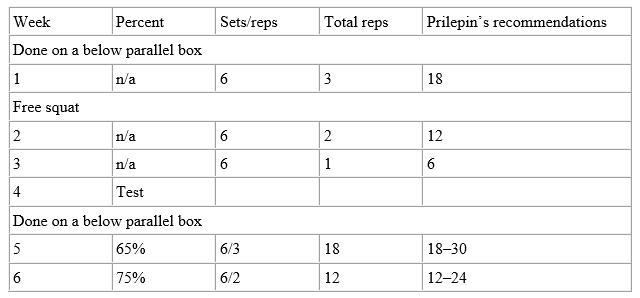

We start off on a box because we feel it’s easier to teach technique and break it down as follows:

Week 1: Both the dynamic and “max effort” workouts are done with a box. Max effort is in quotes because it’s nowhere near the true max effort.

Week 2: We use a box on speed day, which is done first in the week. On max effort day, we take the box away. We remind our athletes that nothing changes. We still sit back, keep our chests up, and go below parallel. We test on free squats because it’s only appropriate to squat in the same manner that you’re going to test.

Once we have a max, we’ll do a three-week wave with the box going up by about 10 percent per week on our max effort day. We start at 65 percent. After this, we go to free squats for three weeks to give our athletes time to adjust to not using the box.

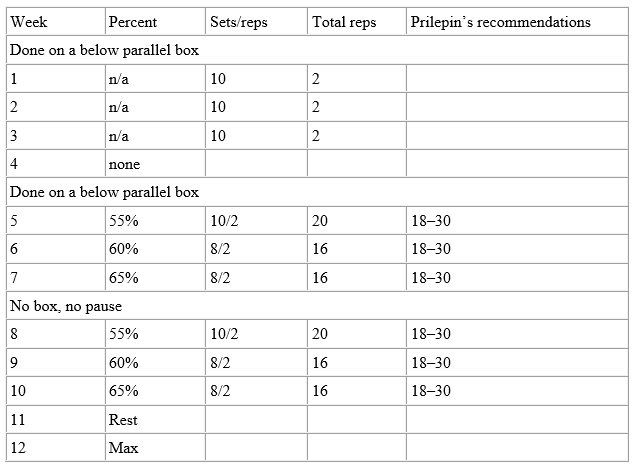

Our max effort day would look something like this:

Max effort day

We adhere to Prilepin’s recommendations. We do keep the total number of reps in a workout toward the low end. The numbers of reps per set are kept low to keep form from breaking down and to provide more coaching time. The athlete does 2–3 reps, and we tell them what they did right and wrong. They then do another set and repeat the process.

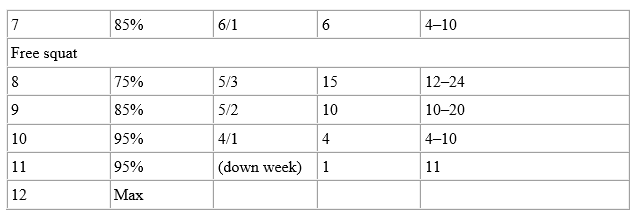

Our dynamic day would look something like this:

Dynamic effort day

Our reps per set on the dynamic day are lower than what Prilepin would recommend. This is based on Louie’s recommendations that you should keep the reps lower than normal to keep the bar speed high. Remember that the experiments were done on Olympic lifts, not power lifts. The power lifts can take longer to perform.

For weeks 1–3, we use a box to help teach technique. Week 4 is a down week (rest.) For weeks 5–7, we use a below parallel box, and for weeks 8–10, we take away the box to allow the athlete time to get use to free squats. Week 11 is a down week. So for the last 3–4 weeks the athlete will do all free squats (no box, no pause). These templates don’t take into account any interruption in training (i.e. non-traditional seasons, etc.).

Probably the most important thing that we emphasize to our athletes is moving the bar fast. If you have an athlete under 70 percent and they move the bar like it is 70 percent, they won’t get a training effect. Personally, my biggest problem when I started using Prilepen’s chart was that I didn’t understand my capabilities. A few ways of combating this is to put the athlete to a stopwatch. Time the concentric portion of the lift only. This always gets them competitive. Have them coach one another. Look at their faces. I’ve never seen someone who pushes with 100 percent effort look pretty. If their facial expression doesn’t change, they’re not pushing hard enough.

I hope this will give coaches a new perspective on training their beginning athletes. If you have any questions on any of the material presented, feel free to contact me at Kontosstrength@mac.com or takontos@vcu.edu.

References

1) Craven M (1994) Personal communication.

2) Laputin P, Oleshko V (1982.) Managing the Training of Weightlifters. Kiev: Zdorov’ya Publishers.

3) Simmons L (2001) HIT…or Miss? Westside Barbell. http://www.westside-barbell.com.